By, Rayma Kumari

Ba.Llb 5th year

Lovely Professional University, Punjab

Co- Author – Dr. Samta Kathuria, Prof. Lovely Professional University

Introduction

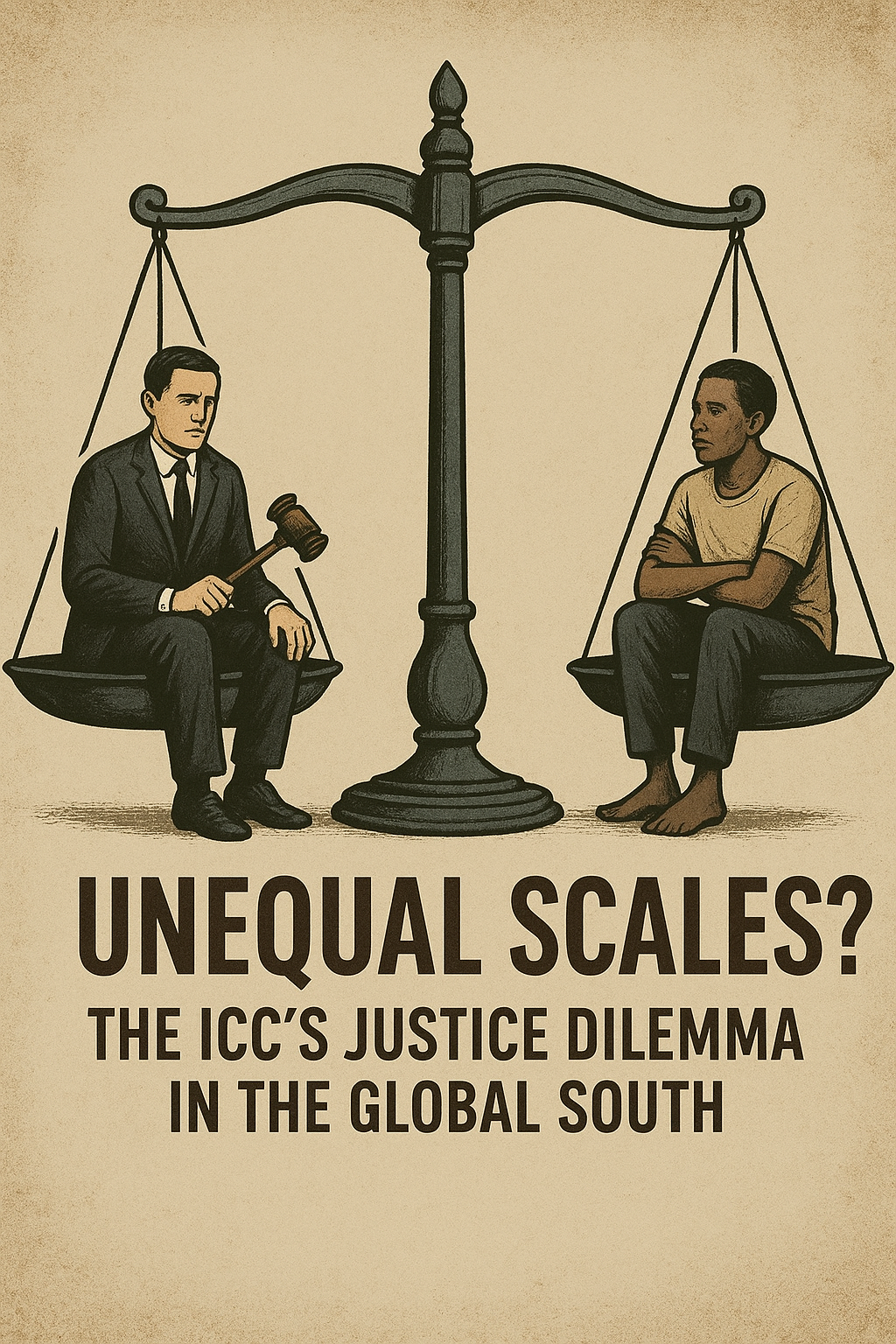

The International Criminal Court (ICC) was founded on the promise of holding perpetrators of the gravest international crimes—genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity—accountable, regardless of status or geography[1]. However, over two decades into its existence, the ICC faces mounting criticism from the Global South, especially from African countries, over accusations of selective prosecution and neo-colonial bias. This debate questions whether the ICC genuinely advances global justice, or simply reinforces power imbalances enshrined in the international order[2]. The Court’s engagement with leaders from the Global South, amid limited actions against powerful Western or allied states, sits at the heart of this controversy. As the only permanent international tribunal designed to try individuals for international crimes, the ICC’s legitimacy, credibility, and effectiveness in promoting justice remain critical issues in global governance.

Background

The ICC was established by the Rome Statute in 1998 and began its operations in 2002. Its founding came after the shortcomings of ad hoc tribunals like those for Rwanda and Yugoslavia, and it was hoped that a permanent court would provide consistent and impartial justice. Notably, African states played a crucial role in creating the ICC. Early support from Africa was strong, and the majority of initial signatories were from the continent. However, the ICC’s exclusive focus on African situations and leaders in its first decade led to growing skepticism and allegations of bias. High-profile indictments, such as those of Sudan’s Omar al-Bashir and Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta, sparked charges that the court disproportionately targeted African countries while powerful nations, including the US, held themselves beyond its reach by not ratifying the Rome Statute. Multiple African states, such as South Africa and Burundi, have threatened or initiated withdrawal, and in 2025, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso withdrew, citing institutional incapacity and bias[3].

The legal foundations for the ICC rest in the Rome Statute, which embodies the principles of complementarity—yielding to domestic prosecutions except where local systems fail—and universality. Yet, the ICC’s ability to enforce its mandates depends on state cooperation, especially for arrest warrants, revealing the limits of its legal power over sovereign and non-signatory states.

Legal Analysis

Selectivity and Legitimacy Concerns

The ICC’s selection of cases is at the core of the legitimacy debate. Since its inception, most of its formal indictments and investigations have targeted individuals from Africa, sparking claims of “justice only for the weak,” while ignoring similar atrocities allegedly committed elsewhere—by or in states enjoying political clout in the global system. Critics argue that, whether by design or by default, this focus mirrors the political realities and power imbalances of global governance, which structures and constrains the international legal order.

Procedurally, selectivity is partly driven by self-referrals, where African governments invited ICC scrutiny of rebel groups, but grew hostile when pro-government forces were investigated. The principle of complementarity is intended to leave local courts responsible where possible, but in practice, weak or politicized domestic systems in the Global South led to ICC intervention, compounding perceptions of external interference and neo-colonialism.

Recent attempts by the ICC to issue warrants against leaders of powerful nations—for instance, Vladimir Putin and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu—have laid bare the court’s intractable enforcement deficit; such warrants remain unenforced, highlighting the unequal implementation of international justice. Many Western states, which once championed ICC prosecutions, have recently rejected the court’s authority when it implicates their allies, further undermining its claim to universality.

Legal and Institutional Challenges

Scholars highlight the ICC’s limited reliance on laws and jurisprudence from the Global South, even when these are relevant. The Court has shown reluctance to apply African legal principles, often insisting on ‘universally adopted’ standards, making it hard for Global South perspectives to be recognized. This results not just in legitimacy issues, but also in a perceived lack of procedural justice, as seen in numerous high-profile judgments.

The court’s legitimacy crisis is intensified by the non-participation of major powers (USA, Russia, China) that have neither ratified nor accepted ICC’s jurisdiction. This selective ratification undermines any claim to impartial justice. The African Union’s calls for collective withdrawal, and recent exits by Western African nations, exemplify broader resistance to perceived judicial imperialism.

Despite these criticisms, some argue that the ICC’s selectivity results not from intent, but from structural and practical constraints. Issues like the need for state cooperation, the principle of gravity, and resource limitations mean it cannot prosecute every deserving case and so often acts where prosecutions are most politically feasible.

Structural and political challenges

The ICC’s relationship with the Global South reflects a broader tension within international law between universal legal principles and political realities. While the Rome Statute enshrines ideals of impartial justice, the geopolitical landscape where these ideals operate is far from neutral. The Court’s dependence on state cooperation means that powerful states can shield themselves or their allies from scrutiny, while weaker states and leaders become more vulnerable subjects of ICC investigations. This asymmetry fuels the perception of the ICC as a tool of geopolitical power rather than a neutral arbiter of justice[4].

Moreover, the concept of “complementarity,” which holds domestic courts primary responsibility for prosecuting international crimes, interacts complexly with the Global South’s often weak judicial systems. The ICC steps in primarily when domestic legal avenues are deemed ineffective or biased. Yet, this intervention can be seen as overriding sovereignty or as a continuation of neo-colonial legal impositions, exacerbating mistrust toward the Court. The tension between respecting sovereignty and ensuring accountability under international law remains a key institutional challenge for the ICC.

Recent developments also reflect shifts in the Court’s strategic priorities. Efforts to investigate situations outside Africa—such as in Georgia, Colombia, and Palestine—signal attempts to demonstrate universality. Nonetheless, the Court’s limited enforcement capabilities persist, as arrest warrants and prosecutions depend heavily on political will and international alliances. This imbalance leads to ongoing debate about whether reforming the ICC’s mandate or bolstering national capacities offers a more effective path to justice.

Finally, scholars argue for a reformed international criminal justice framework that better incorporates Global South perspectives—both in legal reasoning and institutional representation. This includes integrating customary laws and local dispute resolution traditions to enhance legitimacy and effectiveness. Without such reforms, the ICC risks alienation from the very communities it aims to serve and may face declining relevance in global governance.

Balancing Justice and Political Realism

While the promise of a global criminal court remains inspiring, its practice reflects the difficult intersection of law and geopolitics. The ICC walks a tightrope between striving for legal consistency and transparency and navigating a world of political realities where state interests often take precedence over impartial justice[5]. The genuine challenge lies not just in the court’s procedures or the selectivity debate, but in the fundamental contradiction of a global order where enforcement depends on the goodwill of the powerful.

Suggested Solutions and Possible Outcomes

To restore legitimacy, the ICC must demonstrate genuine even-handedness. This could involve:

– Actively pursuing cases outside Africa, including investigating atrocities involving powerful or Western-aligned figures, where feasible.

– Greater reliance on and recognition of legal traditions and practices from the Global South, integrating them into jurisprudence wherever possible[6].

Increased engagement and communication with affected communities to ensure decision-making reflects local realities and moral concerns.

– Structural reforms, including more equitable representation within prosecutorial and decision-making bodies, and enhanced transparency in case selection processes.

Reforms alone may not resolve underlying structural inequalities, but they could make the court’s processes more transparent and its outcomes more consistent—key ingredients for regaining trust. If the ICC successfully expands its focus, it might gradually rebuild credibility in the Global South. Conversely, continued perceptions of bias may hasten withdrawals and sideline the ICC’s influence further in the international justice system.

Conclusion

The legitimacy of the ICC stands at a crossroads, shaped by a legacy of selective prosecution and the persistent realities of geopolitical power imbalances. Ensuring universal justice within an unequal global order remains a profound challenge, but the ICC’s efforts at reform and broader accountability are essential steps for international organizations seeking to maintain relevance in global governance. The path forward lies in transparent, inclusive, and principled legal processes, anchored by the recognition that impunity anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

References

1. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court:

(2002). The United Nations Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. International Organizations. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/lcwaN0018822/

2. ICC Case Example (Prosecutor v. Lubanga Dyilo):

Prosecutor v. Lubanga Dyilo (Judgment) ICC-01/04-01/06 (14 March 2012).

3. United Nations-ICC Relationship Document:

United Nations. (2004). Relationship Agreement between the United Nations and the International Criminal Court (UN Doc. A/58/874 + Add.1).

4. African Union Declarations on ICC (example):

African Union. (Year). Declaration on the International Criminal Court and its impact on African countries.

[1] The International Criminal Court: Current Challenges and … https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2580&context=jil

[2] ICC’s Double Standards: A Court for the Powerful or Against the … https://shabellemedia.com/iccs-double-standards-a-court-for-the-powerful-or-against-the-weak/

[3] Rethinking the International Criminal Justice Project in … https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/rethinking-the-international-criminal-justice-project-in-the-global-south/

[4] Reframing the ICC Selectivity Debate? The Importance of … https://justiceinconflict.org/2018/04/24/reframing-the-icc-selectivity-debate-the-importance-of-consistency-and-transparency/

[5] The ICC, feminist geopolitics and alternative legal futures https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/geoj.70026

[6] (Non-)Use of African Law by the International Criminal Court https://academic.oup.com/ejil/article/34/3/555/7236903